Step back in time with me to the late 1860s. The popularity of billiards is on the rise, but there’s just one problem – the game is putting a strain on the global supply of ivory. Yes, that’s right, pool was causing the mass slaughter of elephants so their tusks can be turned into balls.

Printer turned inventor John Wesley Hyatt, responding to a $10,000 reward offered by a New York firm, discovered treating cellulose, that he derived from cotton fiber, with camphor, created a plastic that could be formed into a variety of shapes. Elephants around the world breathed a (brief) sigh of relief.

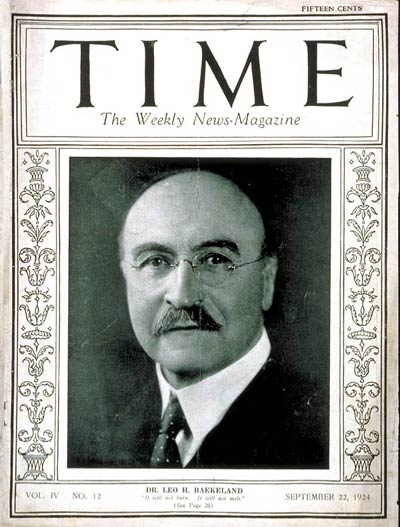

Almost 4 decades later chemist Leo Baekeland created the first fully synthetic plastic, Bakelite.

Until the invention of Bakelite, Baekeland was best known for his invention of the first commercially successful photographic paper, Velox. The story of how Baekeland jumped from photographic paper to plastics is interesting and offers a minor indictment of capitalism in and of itself.

The son of a cobbler, Baekeland received his education in Belgium; and then took advantage of a travel scholarship to visit universities in England and the United States. The young chemist was convinced to stay in the US and further his work on photographic paper for the Anthony Company. In 1891 he became self-employed choosing to work as a consulting chemist. Illness created financial stress for him and his family (sound familiar?) and he went back to work on his photographic paper. Unfortunately, his breakthrough came as the U.S. was suffering a recession and investors and buyers for his improved photographic paper. Eventually, he formed the Nepera Chemical Company with Leonard Jacobi, which the pair sold in 1899 to the Eastman Kodak Company. Baekeland earned approximately $215,000 but was prohibited from continuing to research and innovate in the photographic paper space as a condition of the sale (that sounds more like capitalism embracing protectionism than innovation to me…).

Financially stable, Baekeland purchased a home and set up a well-equipped laboratory in Younkers, New York. He’s recorded in the National Academy of Sciences biographical memoirs saying, “in comfortable financial circumstances, a free man, ready to devote myself again to my favorite studies… I enjoyed for several years that great blessing, the luxury of not being interrupted in one’s favorite work.”

Capitalism Didn’t Innovate to Create Plastic

Capitalism was perfectly fine with the mass slaughter of elephants to create billiard balls. The companies engaged in manufacturing pool balls didn’t look for a sustainable or humane alternative to ivory, it was an independent inventor.

Synthetic plastics came into being because a financially comfortable chemist was able to invest his time, energy, and problem-solving passion into synthetic resins. Yes, Baekeland was drawn to synthetic resins because of his desire to make money, but no capitalistic corporation was investing in this research at the time. Capitalism was content with business as usual.

The transformational effect that plastics have had on society is hard to understate. There’s no question that these polymers paved the way for advances in medicine, delivered safe drinking water to hundreds of millions of people, and created the creature comforts many of us have come to take for granted.

How many brilliant chemists are unable to pursue their passions because they’re working a menial corporate job to pay off a mountain of student loan debt? How many women never pursued their interest in science because of capitalism-driven workplace discrimination in STEM fields? How radically different would our world look if society guaranteed everyone’s basic needs are met giving them the freedom to be innovative and creative?

Capitalism is Lazy, Wasteful, and Refusing Innovation to Solve the Plastics Crisis

For all the blessings of plastics, there’s also a downside – a steep downside. The plastic crisis has been made exponentially worse by capitalism’s unimaginative and stingy pursuit of profit. Under the stewardship of capitalism, plastics have turned into an unmitigated environmental disaster.

Here’s a fun lie that capitalism tells you in order to preserve their bottom-line: some plastics just can’t be recycled. Blatantly false. While there are limits to mechanical recycling of plastics, using a chemical process to split the polymer chains back to their most basic state means all plastics can be recycled.

Of course, chemical recycling costs more and currently is a more energy-intensive process than mechanical recycling. On the surface…

…If we took into account the true cost of manufacturing pristine plastic and the environmental toll of discarded plastic chemicals recycling makes a lot more sense – but neither of those factors is easily shown on a company’s balance sheet.

Capitalism didn’t give us plastics and it’s actively standing in the way of solving the plastics crisis. Fixing the environmental devastation brought on by capitalism’s wasteful excesses and complete disregard for the common good will take innovation this economic system has proven time and time again that it is incapable of delivering.

Make a Difference

There are many organizations working to remove plastic from the environment. If there’s a group in your area, support their local efforts! If you’re the type that likes to organize people for action, organize a community or neighborhood pickup – Earth Day is April 22 this year.

Of course you can always donate to a larger organization (just check Charity Navigator before giving).